Background

Abuse of prescription pain medicines is the leading cause of injury-related death the US (CDC 2015). The vast majority (74.8%) of individuals who abuse pain medications report that they receive them either directly from a physician’s prescription or for free from another individual who received them directly from a physician’s prescription (NSDUH 2013). Compounding this issue, objective data suggests that the UK Trauma and Acute Care Surgery Service is not adequately treating pain, as evidenced by only 10% of survey responders reporting adequate pain control while under the care of the Blue Surgery Team (HCAHPS 2014). While opioid pain medications may be considered the most effective means of pain management due to the theoretical lack of a ceiling effect for analgesia, the use of multi-modal analgesia including anti-epileptics, anti-spasmodics, and anti-inflammatory agents is more effective than reliance on a single modality (American Pain Society 2008). For these reasons, the current pain management protocol has been revised to provide a decreased reliance on opioid medications with an increased reliance on adjunctive therapies to improve pain control and patient safety.

Pharmacology

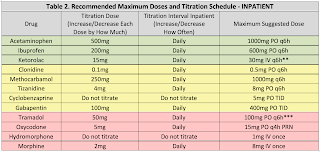

For typical dosing and titration parameters, see Table 1. The information below is intended to help guide selection of adjunctive medications using patient information.

Acetaminophen (APAP) is an effective analgesic and antipyretic typically co-formulated with opioid medications for reasons previously discussed. In overdose, acetaminophen can cause hepatotoxicity due to buildup of a toxic metabolite, NAPQI. The FDA mandates APAP doses should not exceed 4gm per day. Use is discouraged in patients with acute hepatitis and decompensated cirrhosis. Use has not been linked to dependence or abuse.

NSAIDs are anti-inflammatory analgesics and antipyretics that are also co-formulated with opioid medications for a synergistic effect. Through COX-1 inhibition, Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) may alter platelet function; therefore, use is discouraged in patients with severe thrombocytopenia. NSAIDs have been associated with increased rates of nonunion and infection in patients with fractures (particularly long bone and spine fractures), and caution with use in this population is encouraged. NSAIDs may alter renal blood flow through prostaglandin inhibition, which may result in an inability to dilate the afferent arteriole of the glomeruli, and use in patients with acute kidney injury or severe dehydration is not recommended. Finally, NSAIDs may increase patients’ risk of developing gastrointestinal ulcerations and use should be avoided in patients at high risk. Concomitant use of PPIs has been shown to decrease this risk, which is greatest with NSAIDs that have higher COX-1 selectivity (e.g., aspirin, ketorolac). Use has not been linked to dependence or abuse.

Clonidine is an alpha-2 agonist that acts via inhibition of microglia and signal-related kinase activation and may decrease adrenergic response to pain. Further, there is evidence that both clonidine and dexmedetomidine have opioid-sparing effects (Blaudszun, et al. Anesthesiol 2012). Use is associated with hypotension, so in hemodynamically unstable patients use is discouraged. Transdermal clonidine is no more effective than oral, takes longer to show an effect, and is substantially more expensive. Use is therefore discouraged in most patients. Use has not been linked to dependence or abuse.

Skeletal muscle relaxant (SMR) use can be associated with significant drowsiness; therefore these medications should generally only be used for patients who are refractory to other, less sedating modalities or those with significant muscle spasm. Cyclobenzaprine is associated with a higher risk of sedation than other SMRs, and data suggests doses above 15mg per day offer no additional benefit, with only additional sedation (Borenstein, et al. Clin Ther 2003). Although not a controlled substance, cyclobenzaprine has been associated with abuse and misuse (NFLIS, STRIDE 2012). Other muscle relaxants such as tizanidine and methocarbamol may be less sedating alternatives to cyclobenzaprine. In general, SMRs should be avoided in the elderly (>65 years old), and long-term concomitant use with opioids is discouraged.

Gabapentin is a GABA analogue initially approved as an anti-epileptic, but now commonly used for neuropathic pain. There is concern of data manipulation regarding the effectiveness of gabapentin for neuropathic pain (Vedula, et al. NEJM 2009), however non-industry sponsored reports still maintain the effectiveness of gabapentin as an opioid-sparing agent. Use is associated with dose-dependent sedation and GI distress; therefore, doses should generally be started low. Abuse of gabapentin in select populations has been reported (Reccoppa, et al. Am J Addict 2004), and gabapentin is a controlled substance as of July 2017. There is limited data examining combination gabapentin/pregabalin therapy, and use of both drugs concomitantly is generally discouraged. Both drugs have linear dose-response relationships, so higher doses are likely more effective than lower ones. Both drugs are also renally eliminated and require dose adjustment in acute and chronic renal failure.

Opioid analgesics such as morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone still have a role in management of acute surgical and traumatic pain. Because these agents theoretically do not have a ceiling for analgesia (unlike all other classes of analgesics), they are considered the most effective pain medications; however, there is acute pain data available from the CDC that counteracts this argument and suggests opioids are less effective than combination OTC products. All opioids carry a serious risk of dependence and overdose. Concomitant use with benzodiazepines is strongly discouraged. Use of extended-release preparations is independently associated with overdose risk, and use of these products (e.g., MS Contin®) is discouraged as well. With the exception of tramadol & codeine, all opioids are C-II substances. In patients with a history of substance abuse receiving medical therapy (e.g., buprenorphine, methadone, naltrexone, etc.), their home medication should generally be continued on admission. Consultation with a pharmacist and/or pain management is strongly recommended.

Tramadol has the added benefit of serotonin inhibition and mild NMDA antagonism, potentially making more beneficial than other opioids. It is less potent than other opioids, but is equally effective at equianalgesic doses. Tramadol has less abuse potential than hydrocodone.